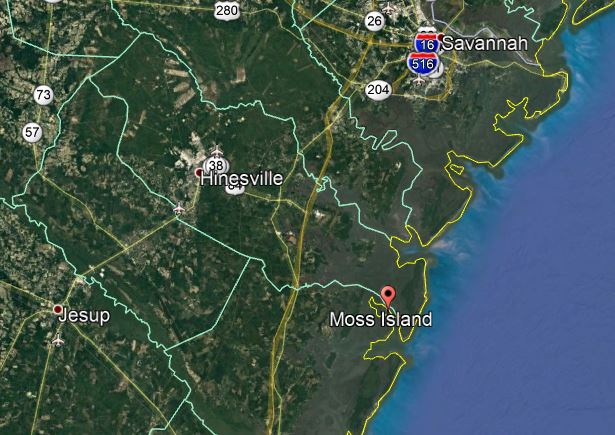

In 1804, two of my ancestors, John and Sarah Ashmore, were farming on a small island called Moss Island in the South Newport River, just inland from the Georgia coast, near what is now the Harris Neck Wildlife Refuge. They had four children: Joseph (13), John (10), Sarah (3), and Elizabeth, an infant. Two children, Rebecca and Ann, had already died in infancy. For those of you who don’t know coastal Georgia, it can be a harsh environment: gorgeous with its huge live oaks draped with airy Spanish moss and spectacular marsh views but vicious mosquitoes, biting gnats, poisonous snakes, alligators…well, you get the picture. Coastal Georgia is also right at — sometimes below — sea level.

In late August of 1804, a violent hurricane swept across Jamaica. According to Walter Fraser in his book Lowcountry Hurricanes, it was the first great storm of the new century in that region. It destroyed every ship in the harbor at St. Kitts and sank 56 of 58 vessels in the harbor at St. Bartholomew and 26 of 28 at Dominica. The waters were warm, and it strengthened as it moved north and curved toward the American coastline. On September 6 and 7, it hit St. Augustine, Florida, and sank all but one of 10 ships in the harbor. By Friday, September 7, Fraser described it as an “immense tropical cyclone” that was still miles offshore but soon would “simultaneously envelope large portions of both Georgia and South Carolina.”

The wind was starting to whip through the Georgia and South Carolina coasts on September 7. Major Pierce Butler’s plantation on St. Simons Island, GEorgia, was playing host to Vice-President Aaron Burr, who was hiding from federal authorities after his duel with Alexander Hamilton.

By Saturday, September 8, everyone along that coast knew they were in for something, but what? The Ashmores on tiny Moss Island were unknowingly right in the path. That day, as the wind howled and whipped up waves in the river, they must have been fearful, but without all the modern technology that tells us today what to expect. Similar weather had happened before without damage.

But that was not to be their fate. Let me continue in the voice of the Rev. Charles Colcock Jones, who told the story at Sarah’s funeral in 1847: “The water driven in by the storm overflowed the entire island & washed away every vestige of the settlement. Mrs. Ashmore lost a child from her arms & two others were drowned. She floated ashore on a part of the house, as did Mr. Ashmore & his son Joseph & a servant, neither of them knowing that another done survived. On reaching the shore – when the storm somewhat abated – Mr. Ashmore [w]hooped hallo, hoping against hope, that some one of his family might have been preserved. Some one answered him. And making his way through the storm & water, drifted trees & sedge, to his inexpressible joy, he discovered his wife. Their thoughts then turned upon their children. He [w]hooped again & was [1 word] answered by his son Joseph & a servant woman. He collected them together & they were all that remained alive! They had, by the Providence of God, lost every thing they possessed in this life! But although they had escaped a watery grave & had met with so heavy a loss & such deep affliction, yet their hearts were not turned to God & they passed through it all without any permanent or saving change in their character!“

“Mr. Ashmore set immediately to work & put up a small house on the mainland & they were enabled through the kindness of friends and neighbors to get along for the coming year. Mr. Ashmore with his servant went back in the spring & planted a crop on Moss Island, leaving Mrs. Ashmore in their new home. With a cheerful heart & true energy & independence she went into the field around her house – & without any assistance & with her own hands, she raised provisions enough to support the whole family for the year & something for market.”

You may be wondering about the “servant woman.” She was an enslaved woman. I don’t know how many enslaved people were lost that day on Moss Island but Walter Fraser tells us that 70 alone were drowned at nearby Broughton Island. Their stories — of course — are lost to us. From my research, I believe that enslaved woman on Moss Island was named Sibby. Five years later, John Ashmore impregnated her and fathered a child who was named Toby. Sibby’s modern-day descendants and I know that because of DNA, which reveals to us that the same individual can both suffer a terrible tragedy and inflict great tragedy on others.

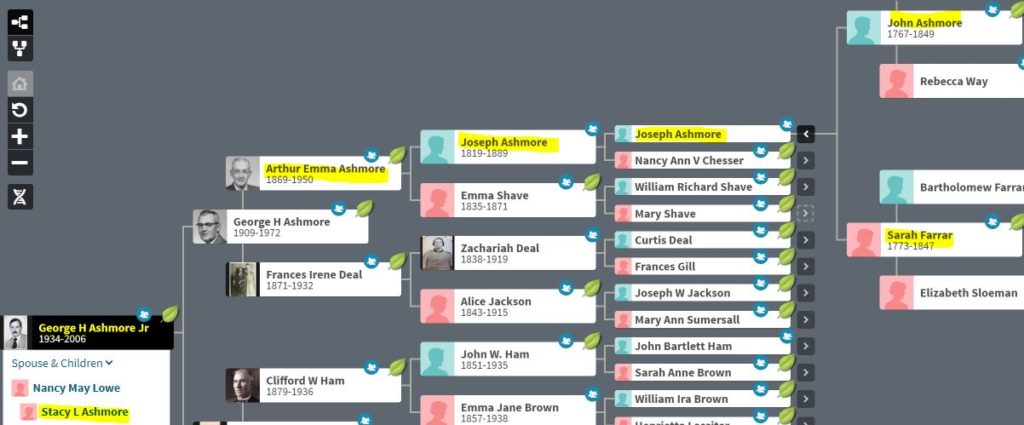

So, Joseph — the child who survived? Who lost his younger brother and two sisters all in an instant? He grew up to be my 3d grand-father.